Mobility

Outside my office window at CSU, I can see the Latin, “Mobilitas Aequat Valetudinem,” or “Movement Equals Health” artfully etched in the concrete. Should it be “Mobilitas Aequat Omnia?” — “Movement Equals Everything”?

Humans move, it’s what they do.

In the early 1900’s the Nobel Laureate neuroscientist Sir Charles Sherrington said “To move things is all that mankind can do, whether in whispering a syllable or felling a forest,” a statement that conveys the truly existential importance of activating muscle and executing movement. To communicate thoughts, express emotions, to move about, to care for others, to eat, to work, to play. Just think about it: If you can’t voluntarily activate any muscle at all, the impact is enormous. Complete paralysis is an admittedly extreme example, but this thought experiment can perhaps deepen our appreciation of the effects of aging on movement and thus on human lives.

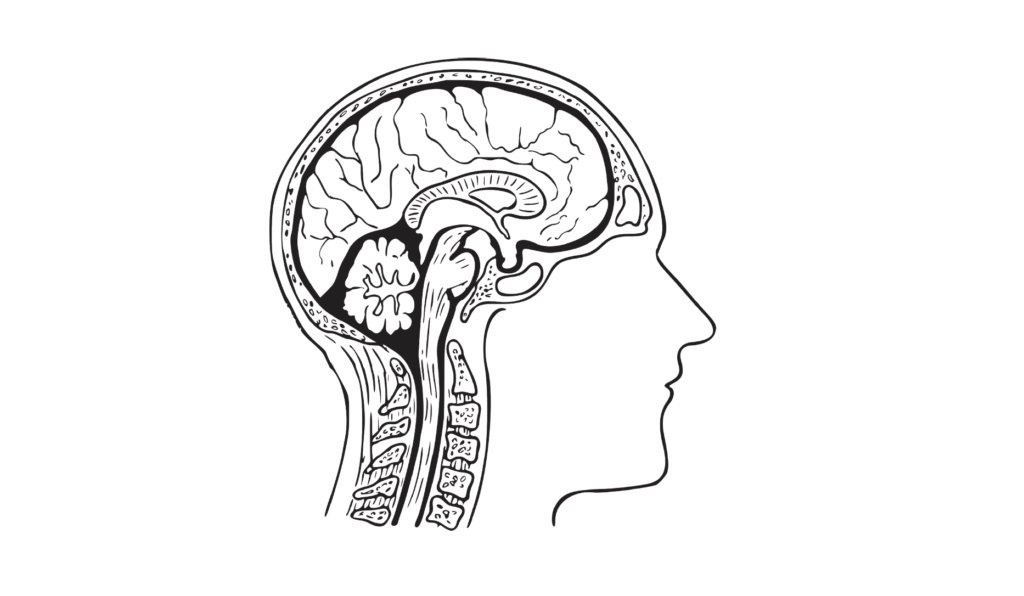

Nerve cells and muscle cells make you move.

Even a simple wag of the finger on your smartphone (much less swinging an axe or throwing a fast ball) requires outgoing motor messaging: activation of billions of brain neurons, hundreds of thousands of spinal cord neurons, hundreds of motor neurons connecting to muscle, and tens of thousands of muscle fibers. And, precise incoming sensory messaging informs the brain of the physical result of that outgoing motor signal: many hundreds of sensory cells in the finger, tendons, joints and muscle, activating thousands of spinal cord cells and billions of brain cells that interpret the signal. Every. Single. Act. Requires. These. Cells.

Mobility is fundamental.

Clearly, mobility is key to quality of life. Unfortunately, aging reduces mobility. We aren’t talking about losing your full-court basketball legs. Rather, it’s the basic daily stuff. Can you carry your groceries up the stairs? Can you get out of a chair, bathtub, or bed? Can you walk a reasonable distance safely? The transition from independent living to frail dependence abruptly and dramatically alters quality of life. In this era of disagreement, we can surely all agree that delaying the loss of independence and reducing the prevalence of this transition is better for individuals, families, and society.

First, the bad news.

Aging deteriorates neurons and muscle.

Brain, spinal cord, nerves, and muscle are the tissues of interest here. Think about the body as the “host environment” for neurons and muscle. Far from the host-with-the-most, in a variety of ways the normally aging human body becomes a less hospitable environment for these cells. Neurons are lost over the years, both in the brain and in the “motor” neurons that connect out to muscle. In advanced age the loss can be substantial. Also reduced is the richness of the neuron-to-neuron and neuron-to-muscle connections. All of this impairs processing, reduces signal strength and speed, and increases the fluctuation (variability) of the signal going out to muscle. In addition, sensory neurons are lost and the precision of their function is impaired in aging, reducing the quality of the important incoming information to the brain.

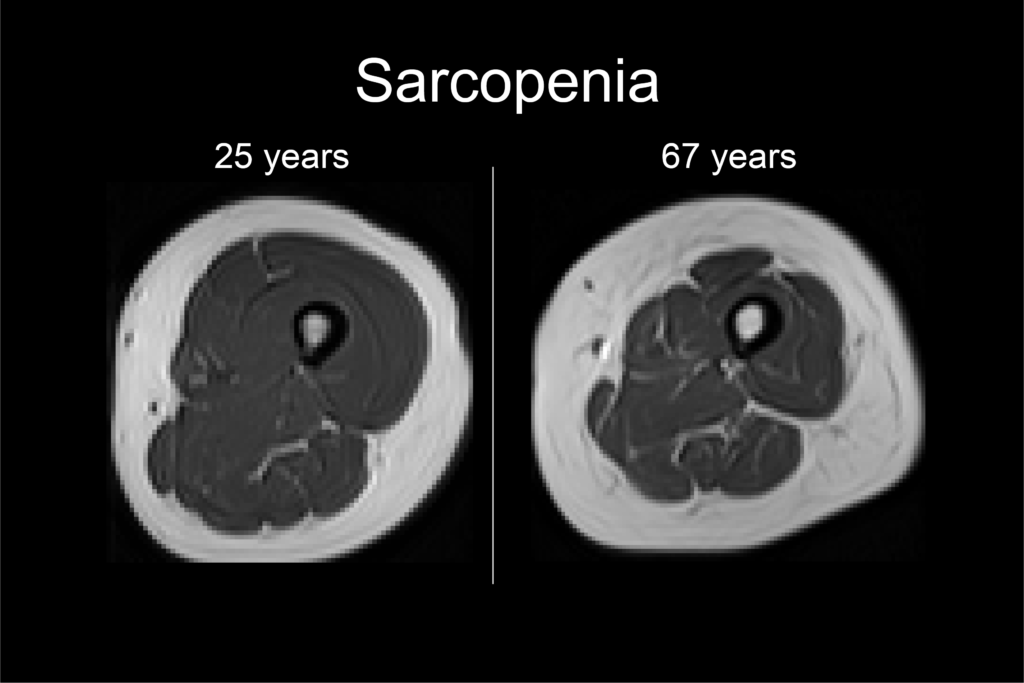

Muscle tissue also deteriorates in the latter decades of normal aging, including 1) a progressive loss of the number of fibers, 2) a reduction in the size of fibers (atrophy) and the size of the whole muscle (a body-wide phenomenon called sarcopenia), and 3) a significant slowing of contractile speed. These are the hallmark changes of neuromuscular aging – smaller, weaker, slower muscles.

Movement quality in aging

Owing to the progressive changes described above, functional limitations can become increasingly impactful for older adults over the years. Muscle strength can decrease by as much as 50% from 25-80 years of age and impair the ability to move the body effectively and perform activities of daily living that require significant muscle force. Speed, also, can be key to success. Slowing of brain processing, nerve signaling, and muscle contraction leads to a reduced ability to do two things at once (dual tasking), react rapidly to a slip or trip to prevent a potentially disastrous fall, or powerfully rise from a chair without stalling. Another less appreciated but very important functional change is impaired coordination and control of the variability of muscle force. For an older adult this can mean an impaired ability to produce muscle force steadily, move the limbs smoothly and accurately, and maintain postural stability (balance) in order to move about effectively and avoid falls.

Enough with the bad news.

The host environment can be changed!

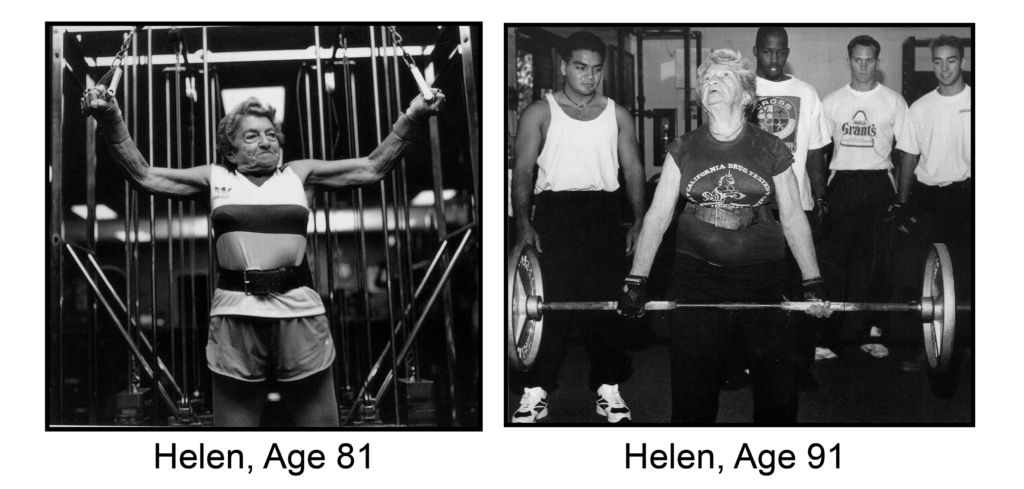

Intense exercise will hurt older adults. Weight training? Grandma will hurt herself. The brain and muscles of older adults can’t respond to training very much. Versions of this thinking persisted for too long in medicine and geriatrics. Importantly, an enormous volume of research in the last several decades has definitively shown that the nervous system and muscles of older adults exhibit substantial plasticity (capacity for change) in response to an exercise stimulus.

Here, we will limit the discussion to strength training. It became clear in a famous 1990 study that even the oldest of the old, frail 87 to 96-year-old nursing home residents with disabling functional limitations, could respond to safely applied strength training with increased strength, muscle growth, and functional improvement in daily activities. And, hundreds of other good studies of older adults have clearly demonstrated improved strength, muscle speed/power, improved daily function, and improved control over the variability of muscle force. Thankfully, there is now no doubt about this in the field of geriatrics.

Let’s be realistic. And optimistic.

Even though the “host environment” can be variously modified and tissues can thus be protected through healthy diet, regular exercise, and weight management, we don’t carry an illusion that all age-related change can be prevented. You’ll never be 25 again (sorry). But, it is clear that regular training can slow the loss of nervous system and muscle function. Perhaps, then, the larger public health goal of this sum total of individual behavior is to delay the transition from independence to dependence and to do so for as many people as possible. This extension of health span (years of healthy life) would save our society billions of dollars a year in health care costs and produce a positive impact on the quality of human life.

TIPS

Training throughout the lifespan, but especially for older adults to delay frailty, should include:

- A regular “strength” training stimulus to all of the major muscle groups, but especially focused on the lower body to preserve muscle mass, maintain locomotion, and enhance mobility.

- Safely performed exercise and movements that feature speed and power, which will help maintain the ability to rapidly respond to unexpected perturbations of body position and prevent falls.

- “Functional” movements, controlled movements, and movements that require flexibility – those required during life. Chair rise, walking, challenging balance exercise, Yoga, Tai Chi.

- Diet and exercise habits that prevent accumulation of fat mass, which plays a large role in deterioration of the host environment for neurons and muscle.

Mobilitas Aequat Valetudinem. Mobilitas Aequat Omnia. Exercise is Medicine.

About the Expert:

Brian L. Tracy, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor in the Department of Health and Exercise Science at Colorado State University. He has performed research for over 20 years on the effects of aging and training on neuromuscular function. More recently his laboratory has been exploring the use of smartphone devices as remotely deployable movement sensors during functional tasks in young and older adults, and in the realm of cannabis intoxication. He has taught CSU courses in the areas of kinesiology, neuromuscular physiology, and innovative teaching neuromuscular lab techniques for over 17 years, and for eight years has been the director of Muscles Alive!, an experiential neuroscience education program for kids from 5 to 95 years of age.