Metabolism

The term metabolism describes all biochemical reactions that occur inside of our bodies to maintain life. There are two sides to the metabolic coin: catabolism and anabolism. Catabolism refers to the breakdown of nutrients to supply energy to support all bodily functions, such as muscle contraction during exercise. Anabolism refers to metabolic pathways that lead to the synthesis of molecules, such as muscle protein.

Aging and Metabolism

As we age, metabolic processes do not operate as well as when we were younger. Our bodies do not metabolize nutrients from food as efficiently, which can cause blood glucose levels to be elevated, particularly after we consume a meal. And anabolic processes such as building muscle protein become less efficient, so it’s harder to gain muscle mass as we get older. In fact, after age 50, adults who do not exercise lose an average of 0.4 pounds of muscle mass each year.

The Good News

But don’t fret! There are a number of healthy lifestyle strategies that have been scientifically proven to offset some of these effects. Incorporate healthy lifestyle behaviors into your daily life—the results can be powerful! The following is a list of lifestyle strategies and tips that have been proven to powerfully impact the metabolic health of older adults.

TIPS:

1 | Keep Moving

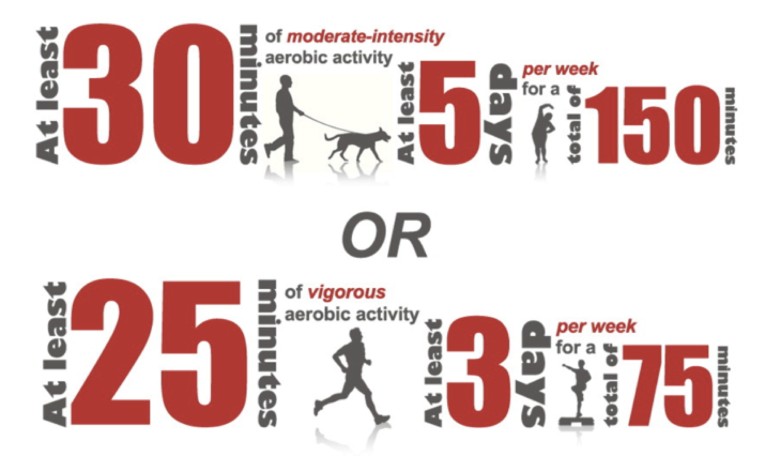

We all know that regular aerobic exercise (a.k.a. “cardio”) is good for our health. Just 30 minutes of at least moderate intensity exercise, five days per week, improves virtually all aspects of metabolic health. But what you may not know is that emerging evidence also suggests that reducing the time you spend being sedentary (a.k.a. sitting) and avoiding prolonged, continuous sedentary periods may also improve your metabolism. Experts report that when sitting is interrupted with short bouts (approximately five minutes) of either walking or standing, important metabolic risk factors, including blood glucose and insulin levels, improve—especially following a meal (so don’t just sit after eating).

2 | Perform Muscle-Strengthening Activities

Muscle-strengthening activities are safe for older adults and proven to maintain the integrity of muscle and bone, and improve balance, coordination and mobility. In addition, because muscles are highly metabolically active, building and maintaining healthy muscle mass will help keep your metabolism going. These exercises may even reduce the signs and symptoms of common metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity. Guidelines from the department of Health and Human Services recommend performing muscle-strengthening activities, such as lifting weights, resistance band exercises or body weight exercise (like push-ups, sit-ups, etc.) at least two days per week.

3 | Consume a Healthy Diet Low in Processed Sugars

To fuel a healthy metabolism you should eat a variety of nutrient dense foods from each food group. Nutrient dense foods are foods that have a high nutrient to calorie ratio such as lean meats, vegetables and whole grains. You should limit processed foods because they can be a sneaky source of added sugar, sodium and “empty” calories—calories that deliver limited nutritional value. Consuming fiber-rich foods and drinking plenty of water may particularly benefit metabolic health by aiding digestion and lowering blood sugar and cholesterol.

4 | Practice Healthy Sleep Habits

As we age, a good night’s sleep can be hard to come by and this is thought to negatively impact important components of metabolism, such as blood glucose levels and insulin sensitivity. The reasons for this are not entirely understood, but experts believe a combination of physiological, environmental and behavioral changes are to blame. Research indicates that the following tips can help promote longer, more restful sleep:

- Follow a consistent sleep/wake schedule.

- Keep your bedroom quiet, cool and dark.

- Avoid blue light before bed (light emitted from TV screens, laptops, tablets, etc.).

- Avoid naps, caffeine, nicotine and other stimulants in the afternoon.

5 | Think Prevention

It’s never too late to benefit from incorporating important health promoting behaviors into your life. However, research indicates that if we start early, we are much more likely to maintain a consistent, healthy body weight, which can be vital for preserving metabolic function, reducing our risk for many chronic conditions and maintaining functional independence well into our golden years.

About the Experts

Kate Lyden, Ph.D., is a research scientist at Misfit, Inc. In this role she designs, implements and supports clinical studies related to physical activity and sleep. She works in close collaboration with academic partners to bring together industry know-how with academic innovation. Prior to joining Misfit, Inc., Kate was a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Her research examined the effects of interrupting sedentary time with short and continuous bouts of moderate intensity walking on metabolic outcomes in overweight adults. She developed methodologies to quantify physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep using wearable sensors, and used these techniques to understand the dose-response relationship between physical activity and sedentary behavior and chronic disease.

After completing his Ph.D. in Exercise Science from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Dr. Edward Melanson started his research career as a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. His research has focused on the effects of lifestyle factors (exercise, diet, sleep) on energy balance and substrate metabolism. Dr. Melanson is currently an Associate Professor in the Division of Endocrinology, with a secondary appointment in the Division of Geriatric Medicine. He is a long time member of the IMAGE research group (Investigations in Metabolism, Aging, Gender and Exercise. Dr. Melanson has published more than 55 peer-reviewed journal articles, as well as 11 review articles and several book chapters. With his collaborators, Dr. Melanson is actively conducting research aimed at understanding the mechanisms via which sleep restriction and alterations in circadian physiology impact metabolism and body weight regulation, as well as mechanisms by which the menopause contributes to weight gain.