Arteries

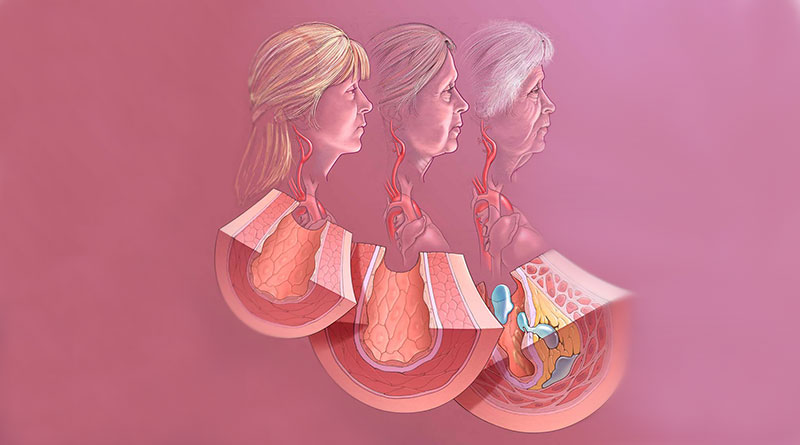

Arteries carry blood with oxygen and nutrients throughout the body. In order to do this effectively, arteries must be elastic, and they must be able to dilate (increase their diameter) to boost blood flow when necessary—like when you perform some physical activity. Unfortunately, two major problems develop in our arteries as we age:

1 | Stiffness

Young, elastic arteries expand and recoil as the heart pumps blood, which helps buffer energy from the heart and drive blood to the rest of the body. However, as we age, our artery walls stiffen, causing increased pressures and altering the flow of blood in ways that can damage downstream organs.

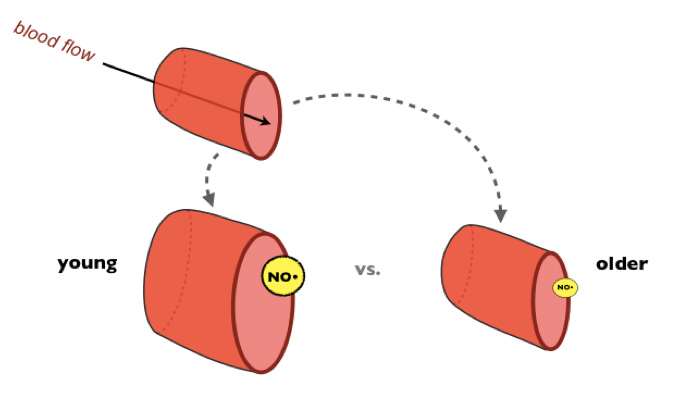

2 | Reduced Dilation

In response to specific body signals, young arteries produce nitric oxide (NO), which causes arteries to dilate so that more blood can flow to areas of need, like exercising muscles. This blood flow allows muscles to produce energy. But, as we age, our arteries produce less and less NO—which means less dilation and less blood flow.

Why does this matter? Stiffer arteries that don’t dilate well increase your risk for heart attack, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases. Dysfunctional arteries also cause other disorders of aging, including cognitive impairments, physical disabilities, and even clinical brain diseases like Alzheimer’s.

TIPS

So, what can you do? Many lifestyle strategies and dietary supplements claim to “support cardiovascular health,” but only a few are scientifically proven. These include:

1 | Aerobic Exercise

Research shows that even moderate exercise increases artery dilation and reduces stiffness—which reduces your risk for many diseases. The American Heart Association recommends 150 minutes per week of moderate aerobic exercise (like brisk walking) or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise (jogging, cycling, etc.).

2 | Watch Your Salt Intake

The recommended upper limit for daily salt (sodium) intake is 2,300 mg (just one teaspoon), and after age 50, it’s less—just 1,500 mg. Meals at many restaurants have much more than that! In fact, the average U.S. adult consumes 3,400 mg of sodium per day. Research shows that when older adults cut their dietary sodium in half, it reduces arterial stiffness and increases dilation by more than 70%. What to do: Try cooking more meals at home using fresh foods, and don’t add extra salt. Also, avoid salty condiments (soy sauce, salad dressings, mustard, etc.) and any packaged and processed foods. You can even rinse canned foods to remove extra salt.

3 | Keep Your Waistline in Check

Most of us tend to put on weight around our midsections as we age. Weight loss is a big topic, but in terms of artery function, it’s simple: that midline weight is important. The American Heart Association classifies a waistline greater than 40 inches for men, or 35 inches for women, as “high risk” for cardiovascular diseases, and older adults in those categories have stiffer arteries that don’t dilate well. But, the good news is that overweight middle-aged/older adults who reduce their waistline by 3-4 inches, increase their artery function to levels similar to young adults.

4 | Keep Your Risk Factors Low

At your yearly physical, your doctor might order a panel of blood tests. You’ll get a list of measurements like cholesterol and blood glucose, and a key that tells you what the “normal” range is for these risk factors. But, the normal range isn’t necessarily safe as you age. Older adults with levels of LDL-cholesterol and fasting blood glucose in the “high-normal” range have worse arterial function than those with low-normal levels. So, read that list closely, and ask your doctor how to keep your risk factors low. For example, people with high-normal LDL-cholesterol and fasting blood glucose who exercise regularly have arteries that function just as well as young adults!

About the Expert:

Douglas Seals, Ph.D., is a Professor of Integrative Physiology and Medicine at the University of Colorado. For 34 years, he has conducted research related to healthy aging, and much of his recent work has focused on prevention of adverse vascular aging and age-related cardiovascular diseases. Dr. Seals’ research is supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and for decades his laboratory has provided training in aging research to students and post-graduate scientists.