Body Temperature

One key challenge we face as humans is to maintain our internal body temperature in the range of 98.6°F (give or take a few degrees). Our bodies function best within a pretty narrow temperature span, and deviations in internal temperature—whether they are caused by stresses like exercise or exposure to hot or cold ambient conditions—can have serious consequences. We cope with these challenges by stimulating a coordinated set of responses aimed at maintaining body temperature within its optimal range. Unfortunately, some of the mechanisms we rely on to regulate internal temperature become less effective as we age. Read on to learn about best practices for managing these seasonal ambient temperature challenges.

1 | Hot Conditions

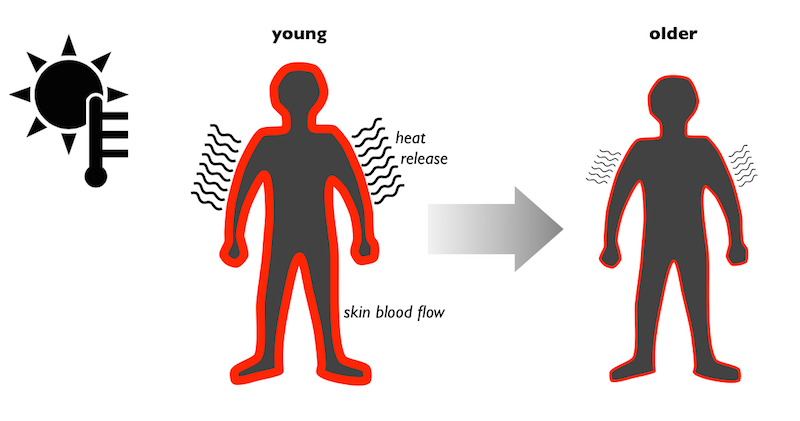

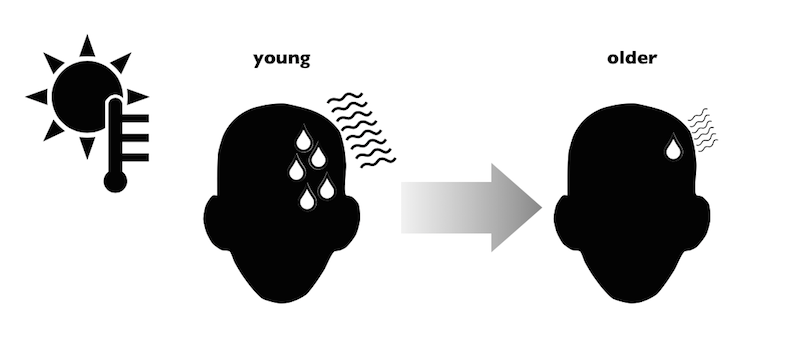

When exposed to hot conditions, sweating is one of the primary methods your body uses to control its temperature. Sweat, as it evaporates, helps cool the skin. Blood vessels feeding the skin also dilate, which allows warm blood to flow to the skin surface. This helps remove heat from the body core. However, these responses are less effective as we age. Our sweat glands produce less sweat and blood flow to the skin is reduced. As a result, our ability to dissipate heat is compromised.

2 | Cold Conditions

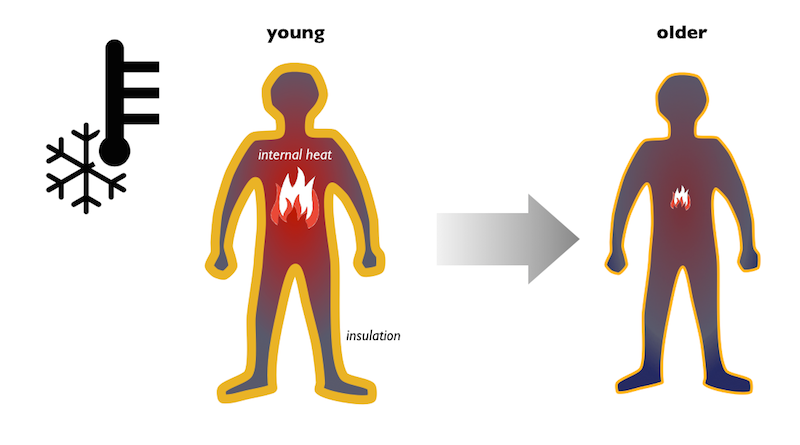

Exposure to cold has its own unique challenges. In an effort to defend body temperature, our bodies decrease blood flow to the skin to reduce heat loss. We also increase internal heat production through several mechanisms. One example is shivering—or the rapid contraction of muscles—which can quickly produce large quantities of heat within the body. But as we grow older, our bodies become less effective at controlling skin blood flow and generating internal heat. In addition, the layer of fat under our skin that acts as an isolator and helps to conserve body heat thins with age. Because of these changes, it is harder for older adults to maintain internal body temperature in the “normal” range in cold conditions.

Why does this matter? A reduced ability to maintain internal body temperature during heat or cold stress can increase the risk for hyperthermia or hypothermia. In addition, coping with these conditions can stress the cardiovascular system, which is also compromised with aging. Thus, when older adults are faced with the combined challenges of temperature and cardiovascular regulation, caution should be observed.

TIPS:

How can you deal with hot or cold conditions as you age? Whether it is exposure to outside temperatures or changes within your living space, here are some strategies to follow that can benefit your overall health and well-being:

1 | What to Do When It’s Cold

Living in a cold space for even a short period of time can cause your body temperature to decline and potentially cause hypothermia. There are several simple steps that can be taken:

- Set your thermostat to at least 68°F to 70°F.

- Wear layers of loose-fitting clothes around the house, and warm clothes when you are sleeping.

- Drink warm beverages, but avoid alcohol, which can increase heat loss from your body.

- Avoid going outside when temperatures are very cold, but if you do venture out, wear appropriate clothing (including a hat, gloves and scarf).

- Remember that people with some underlying chronic health conditions (like diabetes, hypothyroidism and cardiovascular diseases) are more susceptible to hypothermia and should be especially cautious in cold conditions.

2 | What to Do When It’s Hot

Several lifestyle and health factors can increase your risk for hyperthermia. Here are some helpful recommendations:

- Living in a space with air conditioning (in hot conditions) is important.

- On very hot days, stay indoors, and if you don’t have air conditioning, find a space that does (mall, senior center, library).

- If it is necessary to venture outdoors, pick a cooler time of the day (early morning or evening are the best options).

- Drink plenty of fluids throughout the day, as dehydration can have serious consequences.

- If you have existing medical conditions like hypertension, diabetes or Parkinson’s disease, you are particularly susceptible to heat-related injuries and should be extra cautious.

About the Expert

Kevin Kregel is a professor and the associate provost for faculty at the University of Iowa. He earned a bachelor’s degree and doctorate in physiology and biophysics from the University of Iowa, and subsequently performed an NIH postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Arizona. Dr. Kregel has been at the University of Iowa since 1993, and he was department executive officer in the Department of Health & Human Physiology prior to his appointment as associate provost. His extramurally funded research has focused on physiological adjustments to exercise, aging and environmental challenges. He has also been very active at the national level, serving as the chair of committees addressing science policy issues for the Federation of American Societies of Experimental Biology and the American Physiological Society.