Virtual reality program to transform how students learn about the human body

One former student’s simple desire to help his peers better understand how the human body works has unexpectedly grown into a unique virtual reality program with the power to revolutionize medical education.

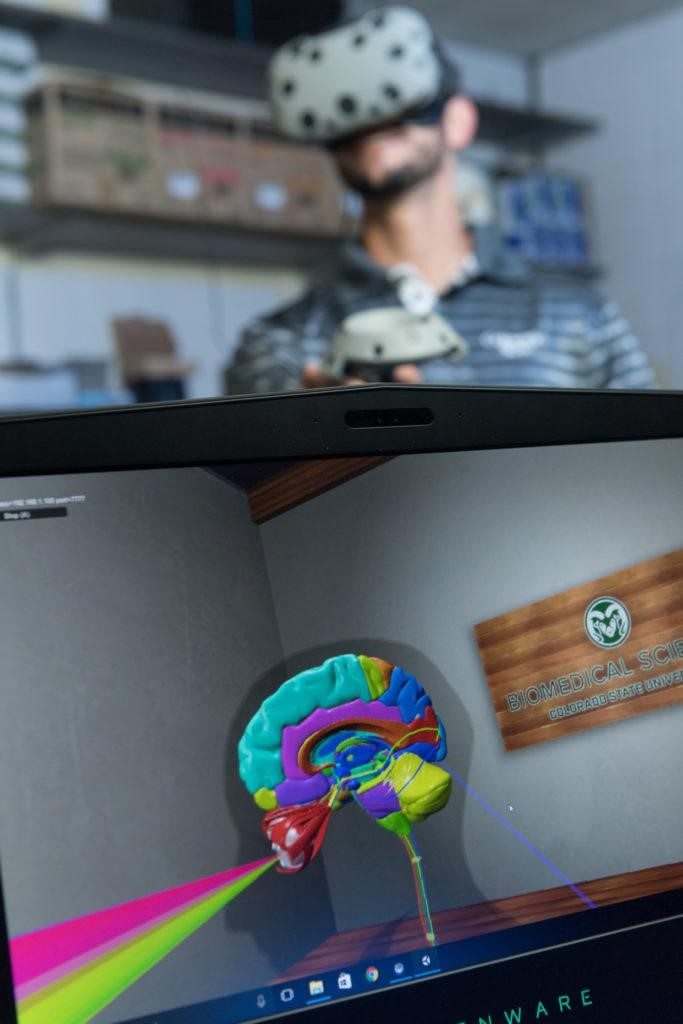

In early 2017, three people in the Department of Biomedical Sciences made it possible to visualize and manipulate magnified models of the human brain and nervous system in all dimensions. The team is now working to expand the program to include all the structures of the body.

The groundbreaking program, with multiple features that set it apart from others, will be housed in the new Health Education Outreach Center and used not only to enhance human anatomy education, but also help CSU become a landmark institution for cutting-edge virtual and augmented reality technology.

A series of fortunate events

When Brendan Garbe, human anatomy teaching lab coordinator in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, was a graduate student, he noticed two kinds of students in his anatomy classes: those who looked at illustrations of anatomical cross sections and immediately understood them, and those who continuously struggled to comprehend how they translated to real life.

“Neuroanatomy students currently learn a lot of structure from two-dimensional cross sections, but they have to picture the systems in 3-D in order to understand complete circuits — I saw that many students had different methods of spatial understanding and couldn’t grasp these concepts from flat textbook pictures,” Garbe said. “I wanted to try and find a novel way to make all of the spatial relationships more intuitive.”

Garbe approached Tod Clapp, an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences and head of its human anatomy program, with his idea to improve anatomy curriculum and began working on it as part of an independent study course. He started by making screen capture videos from an anatomy iPad application in order to better incorporate muscle motions into the curriculum.

Around the same time, Clapp was shown some impressive virtual and augmented reality technology by Kaden Strand, the former virtual reality lead for the Office of the Vice President for Research. When he learned of the Virtual Reality Symposium and Hackathon the office was sponsoring in October 2016 as part of its Virtual Reality Initiative, he talked Garbe into attending.

At the Hackathon, teams had two days to create an immersive virtual experience that includes a teaching, research or outreach component. Garbe’s team won third place with a project showing the interconnectedness of spatial neurologic circuits in 3-D.

“Before going to the Hackathon, I thought virtual reality was just for show and video games,” Garbe said. “Then I put the headset on and realized that I was completely wrong — it’s a night and day difference. The problem is, unless you put the headset on, people can’t describe to you what it’s like — it’s impossible. Even videos can’t get across what it’s actually like.”

After Garbe’s team recreated a very difficult-to-understand neurological system in just 48 hours, Clapp was convinced that virtual reality was worth pursuing. He recruited Chad Eitel, a computer scientist and research associate in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, to be the team’s lead developer in January 2017 — and the rest is history.

“It was very lucky how it all happened,” Clapp said.

On the cutting edge

One of the program’s most powerful tools is its capacity to have multiple people interact in the same virtual space at the same time, providing endless opportunities for students, clinicians, etc. to collaborate, teach and learn.

“What we’re hearing back from people in the industry is that they’re amazed we’ve programmed this in multiplayer, which means I could put the headset on and be in the exact same room as someone in another state or country, in real time,” Clapp said. “And the cross-sectional piece of our program is what any anatomist is going to see and say, ‘OK, it was a neat program until I saw this — now I need it.’”

The team also plans to create interactive lesson plans and teaching modules that will allow groups or individuals to learn from a virtual instructor on demand, as well as virtual lectures that students can access at home using their smartphone and a Google Cardboard headset.

The young program has already led to a variety of cross-university collaborations. In addition to the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, the School of Biomedical Engineering used the program to test the design of a new research device. The team is also in talks with community organizations to create a partnership that would better inform patients about surgery. And, the Department of Biomedical Science’s animal anatomy program used the equipment to test its longstanding Virtual Canine & Equine Anatomy program, which consists of actual anatomical models created by high-resolution photographs. The animal anatomy team is working to move this widely used and successful program into a virtual space in order to make it a more interactive, multidimensional learning experience.

The list of possible applications for the program’s educational features extends beyond medical studies. “We can use this program to visualize anything,” Garbe said. “It’s more about how people can work together, interact and learn. Our initial goal wasn’t to do something in virtual reality, it was to be able to convey information in a way that we didn’t have the tools for until we started using it.”

The program is on track to be fully functioning by spring 2019 and will occupy about 4,000 square feet of space in the new Health Education Outreach Center, slated for completion in December 2018. Fifty stations could accommodate up to 200 students learning in virtual reality at any given time, allowing them to take concepts learned in a virtual space and apply them in the actual lab where they will get the tactile experience of putting it all together.

“I’ve done a complete 180,” Clapp said. “I’ve never been part of something that’s moved this fast or gotten the attention of so many people. When we put students in there, I’m amazed to hear them say how it’s helping them make sense of things. People are a little reluctant to try it out at first, but once they do, within seconds they have a big grin on their face and they will stay in there for half an hour when they have somewhere to be.”

The ‘aha!’ moment

Writer Rhea Maze gets a virtual tour of nerve pathways

Headset on, I watched an avatar of developer Chad Eitel enlarge, shrink and move a virtual cadaver all around the room as he walked me through the visual field, a neural circuit that many students find difficult to learn. The virtual room was bright, clean and inviting, with wooden beams and a high glass ceiling exposing a blue sky dotted with clouds. Colorful lines coursed through the virtual cadaver’s body, representing the routes that nerve pathways travel.

“I once watched Tod Clapp ask his class what would happen to a person’s vision if there was a tumor here,” Eitel said as he placed a gray “lesion” disc onto a section of the virtual cadaver’s brain. As he did so, the colorful representation of its four quadrants of vision clearly showed blindness in one eye. “No one had an answer and everyone was trying to figure it out — but with this program, rather than having to imagine this scenario by studying textbook drawings, students can see how it actually happens in 3-D.”

While I took virtual notes and labeled objects via my hand controls, Eitel showed me an enzyme molecule rendered in 3-D with the help of Aaron Sholders, an undergraduate program coordinator in the Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology. As we walked around it, I flashed back to being an 11th grader and having to spend my lunch hour in “formula club” for bombing a chemistry exam. I couldn’t help but think how helpful the ability to tease apart a molecule and actually see how it interacts with other molecules would have been to me back then.

Others who have tested the program have had similar reactions. “Every physician we’ve gotten in here asks, ‘Why couldn’t this have existed when I was going through medical school?’” Garbe said. “It’s almost always the first thing they say. We believe this could be a cornerstone of medical education in the next decade.”