Diverse Faculty Advancing COVID Research

By Marcela Henao Tamayo

Health care workers often experience frustration when, despite their efforts, resources are insufficient to properly treat their patients. That was my experience while attending medical school in a developing country: I wanted to do more! The best route I found was through disease prevention, a perspective that could potentially have a major impact on human health. CSU’s researchers, community, and facilities offered a unique opportunity for the type of work I wanted to do.

For the past 20 years, I have studied tuberculosis, a pandemic that kills 1.4 million people annually, especially in developing countries. Most of my research has focused on tuberculosis pathogenesis and refining tuberculosis vaccines by elucidating immune mechanisms conveying protection. Even though the currently available tuberculosis vaccine prevents disseminated disease in children, its protective capacity diminishes over time, leading to this tragic death toll.

With time, I realized we needed better tools to evaluate the immune response to infectious diseases and the protective capacity of new vaccines at CSU. Thanks to support from the MIP department, CVMBS, and the OVPR, we launched the Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Facility to address this need. The equipment and expertise of this facility allow us to evaluate how our immune cells respond to vaccines and infection; they can detect infected cells or even assess infectious organisms. We can analyze millions of cells in seconds and examine many aspects of each cell. If required, we can separate a specific type of cell or infected cells at a single-cell level and perform more studies such as sequencing and culturing.

CSU rapidly responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our strength lies in the diverse and vast expertise with infectious diseases and the community’s willingness to work together in a concerted effort, while addressing the pandemic from multiple angles. We have researchers working on candidate vaccines, vaccines that could be easily administered in remote locations or in underprivileged regions, and novel therapeutic drugs or immunomodulators. Some groups are working in epidemiology to prevent dissemination by rapidly detecting the virus in the community; others evaluate different kinds of disease severity and long-term consequences. Many assess how our body responds to this infection and possible explanations underlying differences in disease presentation and severity. Others are investigating the source of the virus and the evolution of similar viruses, including those that could become a health problem in the future. Transmission patterns, the aerobiology of this infection, and its association with climate change are all being investigated here at CSU. We have been fortunate to collaborate with several of these groups. Many research fields have advanced vertiginously: Investigators who had never worked together are collaborating, science that we could not do before is happening, and that is how we know this problem is far from being solved.

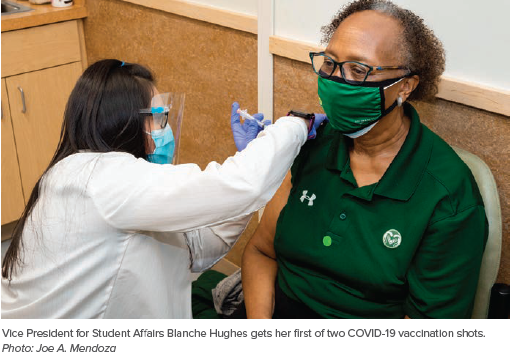

We, as the world, have gone through a steep, often sad, learning curve. The world is interconnected: This pandemic has demonstrated how much we all depend on each other. Several first-world countries and regions in the U.S. now have the privilege of having vaccinated a significant percentage of their population. Unfortunately, the pandemic is not contained until the entire world gets some protection. The world can achieve herd immunity only by vaccination or infection of a high percentage of the population. We hear that message quite often these days. Thus, better efforts to vaccinate disadvantaged communities are needed. We must reach those who don’t have the advantage of understanding the risk they are taking if they don’t get vaccinated; in this pandemic, those are also underprivileged people regardless of where they live. While the virus lives and replicates in any human being, it will keep mutating; it will keep infecting and causing pain and sorrow. There is no way to hide from an infectious disease; we can manage it, sometimes we can shorten it with drugs, but the best way is to prevent it… easier said than done.

Nowadays, teamwork is key to any effort conducive to successful accomplishments. A team of doctors provides treatment for patients in order to get the best care. Researchers from different fields collaborate to investigate novel and better ways of addressing diseases. Governments should listen and consult with those who have experience and think about managing and solving our communities’ problems.

We learned health care professionals and researches should connect and share their knowledge to find the best approach to contain the pandemic. There is no unique voice with a solution, and those who think they have it might be dangerous to the community. A concerted effort to work together with clear goals can prevent more suffering and save many lives.

We need to engage our communities. Science communication is vital; society needs to understand our efforts, our science, and proposed approaches. We should acknowledge and explain to our communities that every field has limitations. Every day we find different, often unexpected, answers to a problem. There are fears in those who “hide” from the advancements in science. Skepticism is often a defense mechanism when we suffer, do not understand the problem, and cannot find clear, reliable help. Could we probably address those feelings and the misinformation through reliable methods of communication? I ask myself constantly how I can motivate people to open their minds to other, probably better, alternatives.

At CSU, many researchers like me, with a passion for life and wellness, work together to address many of the problems our community experiences. We try to push our limits. We educate with love and compassion. Our undergraduates are inspirational, and our graduate students and staff are the best teams we could hope for. I am honored and lucky to be part of this organization.